What we might expect from a UK economy grappling with an extraordinary decision…

At least I am in good company. Along with most opinion polls, the world’s financial markets and even some ‘Vote Leave’ politicians, I confidently forecast to anyone who bothered to ask that the voters of the United Kingdom would opt by a small majority to remain part of the EU in the UK’s referendum on the subject this past June.

It now appears that the UK government itself did not even have a working contingency plan in the event of an ‘Out’ vote, and certainly the major political players on both sides were caught on the hop the morning after.

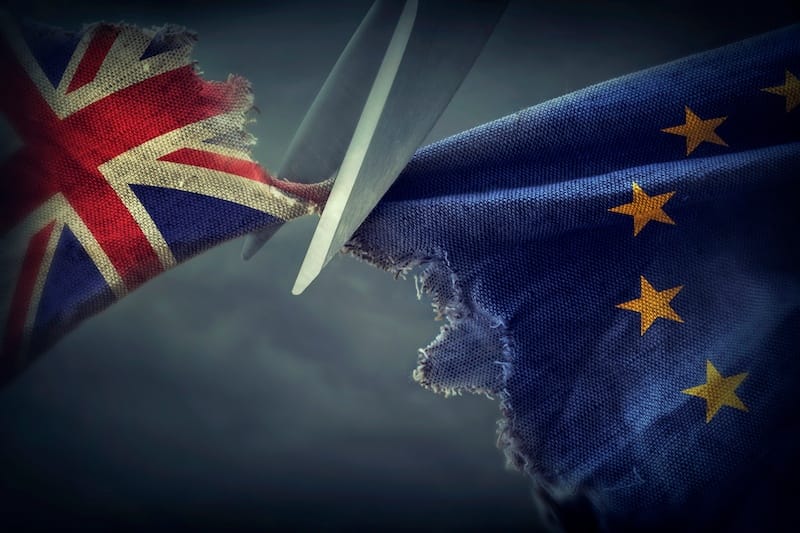

Now that we are a few months on from the British electorate sticking the metaphorical two fingers up to the EU, its own Prime Minister, most economists and business leaders, I am starting to develop some ideas about what the event might mean for the UK economy in general, and the wine category in particular, and what political moves we might expect that will impact our category going forward. Given my now-tarnished reputation as a forecaster, you may wish to stop reading now; perhaps instead, in the interests of traditional Pom-bashing, you’ll cut out and keep this column and wave it at me in a couple of years to illustrate how wrong I was (again).

I’ll start with economics, which affects everything, then look at the wine category, and leave the politics until the end.

In some ways the economic picture is hardest to divine from the data, because it’s too soon to tell. What we do know is that on the day the UK voted to leave the EU, our economy was doing well on most of the core measures. Unemployment was at the lowest level in a decade (4.9 percent), wages were increasing ahead of inflation, GDP growth was bumping along at about 2–2.5 percent, and house prices were still going up.

Wind the clock on a couple of months, and the evidence is decidedly mixed. The latest retail sales data, released as I was writing this column, suggests that the British shopper has shrugged off the shock of Brexit – July sales are up nearly six percent by volume year-on-year, defying most forecasts which had them pegged to decline. The economists are quick to note a number of one-off factors which may have affected this, including a surge in tourism revenue from travellers attracted by the fall in the value of the pound.

The relative buoyancy of the jobs market, combined with the recent cut in interest rates which has put a few more pounds in the pocket of UK mortgage payers, will probably help keep things moving in the short run.

What does this mean for the wine category? The grocery sales numbers are a lot less spectacular – +1.7 percent by volume and +0.8 percent by value, suggesting that prices fell during the period, in large part due to the ongoing price war between the established supermarket groups (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons) and the growing presence of hard discounters such as Aldi and Lidl. This, combined with the 10 to 15 percent decline in the value of the pound against the Aussie and other major wine producer currencies in the weeks, means a nasty margin squeeze in the short term for any major supplier to UK grocery.

Looking further ahead, we think the UK wine market within grocery stores will continue its slow decline in volume terms as low-spending customers exit the category, but we are more confident that value will hold up as the habitual wine drinker grows used to spending £6 or more on an everyday product. The other channels for wine sales – independents, small chains, online, on-premise – will continue to do well on the back of more professional approaches to customer relationships, and a long-running trend towards shopping locally and frequently which is bringing life back to a number of high streets.

The question of what people will be buying – or whether their views on the EU will colour their buying behaviour – is currently hotly debated. We will be asking a question or two on this topic in our October Vinitrac UK consumer tracking survey. The anecdotal evidence so far is that politics is unlikely to be a governing factor in wine choice, though at the margins, a few ideologically-driven consumers may choose to devote more of their spend to wines from the Commonwealth (the only club we would be members of post-Brexit) than stuff from France or Spain.

Finally, we should consider politics, particularly as it impacts taxation and economic stewardship. Effectively the UK now has a new government, though notionally from the same party. The ideology that drove the previous regime centred around improving conditions for business, cutting welfare and walloping high earners on income tax, ostensibly to balance the country’s finances by the end of the decade. For alcohol duty, this meant a broadly sensible approach of freezing the rate or increasing it by relatively small amounts. The good news is that the new regime has publicly abandoned the balanced budget pledge (which was looking unlikely in any case). The more ominous news is that policy on tax, particularly excise duty on alcohol, is now up in the air. Worst case, we could see a return to the punitive ‘Duty Escalator’ of a few years ago, where tax rates would automatically increase by two percent more than inflation.

The longer term political picture is also unclear, because the new government has yet to really show its hand, either on how Brexit will actually work in practice (the leaving date keeps being pushed back – currently 2019 at time of writing), or what philosophy is going to prevail on tax, spending and social policy.

This last element will be closely watched. The government’s statement late last year that it would introduce a ‘Sugar Tax’ to counter obesity was shortly followed by the Chief Medical Officer’s statement in January that there was “no safe level of alcohol consumption”, along with the reduction of the recommended weekly alcohol consumption for men. Both suggested a more draconian policy on alcohol might be forthcoming. However, when the (new) government published its plans for the Sugar Tax, it appeared to be a lot less harsh – no restrictions on advertising or promotion, for instance.

At a fundamental level, the UK is still a strong economy and an interesting market. However, it’s extraordinary how quickly things can change from better to worse. In a world where entrepreneurial talent and capital can easily take wing, the economic dashboard will start to look frightening if Brexit is handled badly and the country ends up with a dysfunctional relationship with the rest of Europe. In such a scenario we can see UK consumers taking fright over uncertainty over future income, or whether or not they will have a job next year, they will quickly rein in spending. This will lead to a shortfall in public finances (VAT accounts for around one-fifth of all tax receipts), which will need to be plugged with extra borrowing (though this might be at higher interest rates because of the UK’s increased risk profile), income tax increases (unwise in a faltering consumer spending situation), or fuel duty (again, unwise in a recession). In this doomsday scenario, governments can be tempted into increasing taxes on alcohol, despite well-documented evidence that this will precipitate a fall in consumption (and therefore self-defeating).

RICHARD HALSTEAD is chief operating officer of Wine Intelligence. Email richard@wineintelligence.com