Considered Australia’s capital of sparkling wine, Tasmania sends its best to Champagne for knowledge and potential links, thanks to the Viticulture Fellowship.

This year, Delamere Vineyards’ Francine Austin has taken out the award, recognising the winery’s innovative viticultural approach and Fran’s personal success as a winemaker. The study trip will be a first for the award-winning winemaker, who hopes to taste some exceptional wines and bring back invaluable knowledge.

“I’m looking forward to the wine of course, but more seriously I’m really looking forward to developing that deeper understanding that comes with first-hand experience of the history, businesses and people that make up a region and a community,” Fran says of her impending trip. “The best growers are doing very well financially there, due to being able to command a high price for their wine, but I want to know how much they credit this to the massive historic investment of the large Champagne houses.”

The fellowship provides Fran with the opportunity to investigate the renowned French region in all its glory, from viticulture and winemaking to marketing and sustainability. Not only is the experience set to be personally beneficial for Fran and Delaware, but with sparkling representing a third of Tasmania’s wine, she also hopes to bring ideas to the greater Tasmanian wine industry.

“Like most in the wine industry, I have a lot of preconceived ideas about Champagne as a region, and I’m looking forward to getting to know her face to face. Tasmania is obviously worlds apart from Champagne, however the production of traditional method sparkling wine in a cold place is complex, difficult and costly, so there is no doubt there will be common ground. Hopefully I will bring back some specific solutions to challenges like managing reserve stock and disease, as well as broader ideas like cross-purpose benefits that can flow between large and small companies within our young industry.”

While Delamere might lack the history of its Champagne counterparts, they share a similar ethos. Located in picturesque Piper’s River (north eastern Tasmania), Delamere exclusively grow pinot noir and chardonnay grapes (60:40 split) on their 6.5 hectare vineyard. They produce a variety of wines, from a selection of sparklings to chardonnay, rosé and pinot noir. “We are trying to create sparkling wines that have a sense of place, much like our pinot noir and chardonnay,” Fran says.

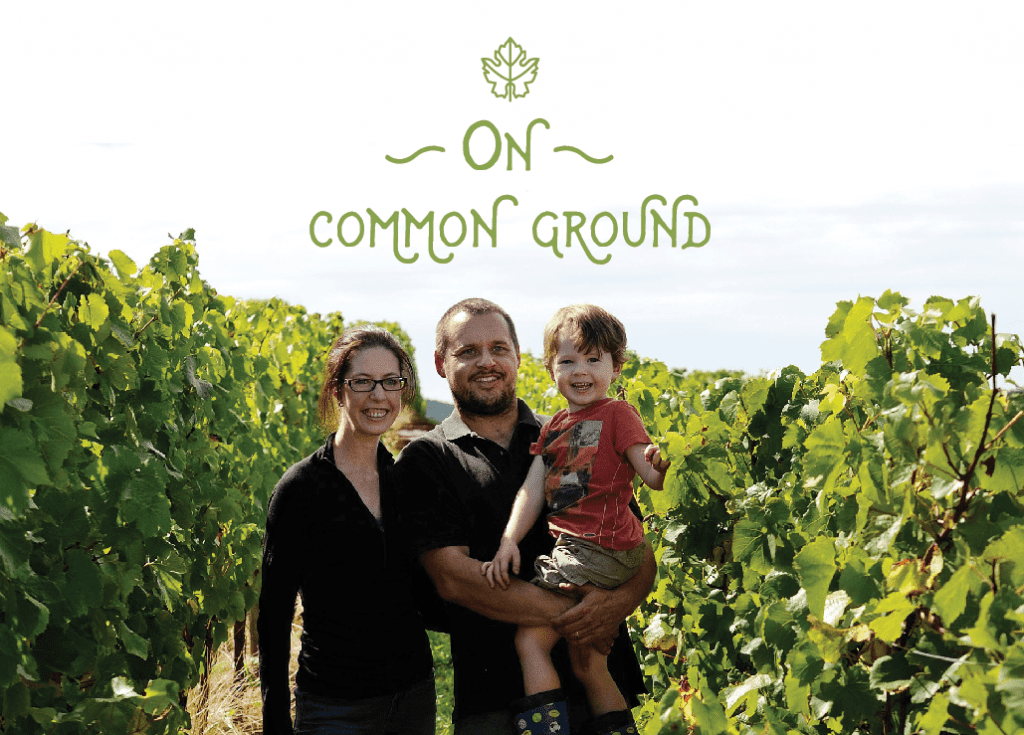

Fran and husband Shane purchased the vineyard in 2007 but the vines themselves were planted in 1982. “It’s among the earliest established vineyards of the modern Tassie wine industry, established based on classic Burgundian principles (low trellis system and about 7500 vines per hectare with 1.2m row spacing) and is dry grown.”

Despite its history-rich viticultural heritage, Shane and Fran made a controversial call to pull out every other vine along each row in the most vigorous sections of the vineyard. “It’s probably the most innovative thing we’ve done,” Shane says. “It took a while to convince Fran, but in the interest of chasing natural vine balance, it just made sense, all emotional attachments aside.”

The Pipers River region is known for its rich, deep red, ferrosol soils, so while every good intention was made when laying the vines out in reference to Burgundy, Shane says altering the row spacing was necessary for optimum growth. “The dense planting format isn’t effective in sections of the vineyard where the soil is deepest – mostly through the middle of the hill. There is no competition between the vines as the roots just keep going down. This leads to crowding as the vines will still grow very vigorously. Pulling every other vine along the rows in these sections has allowed the vines to spread out their growth and has led to much better natural balance and better depth of flavour.” He says the spread-out vine balance can also help reduce the potential for disease in high rainfall years.

But the region’s rich, dense soil also comes with its fair share of benefits, combatting the effects of the inclement weather; high rainfall and drought causing little impact on the vines. “Even in very dry years such as 2009 and 2010, our canopies had no trouble holding on and ripening the fruit, despite being unirrigated. The richness of the soil also means deficiencies in nutrients are small and gradual, allowing for a soft-handed approach to any corrections.”

With this in mind, Shane and Fran have chosen to manage their entire vineyard predominantly by hand. “The trellis is all vertical shoot positioning, with cane pruning and a mix of single and double cordon. Pruning is all by hand, we do early shoot removal, a couple of runs of desuckering and wire lifts by hand. In most years, there are some sections that require some leaf plucking for balance, which is also done by hand. All our fruit is also hand-picked,” he says.

While every care is taken to look after the vines as well as possible, Tasmania – and in particular the Piper’s River region – is prone to very challenging, cold conditions. Shane says because of the differing climatic and soil conditions, we should start to explore subregions in Tasmania. “Cool climate is a concept that’s bantered around the industry quite readily, but it’s become quite evident that we’re seeing diverse styles of vineyards through here; the subregions of Tasmania are really starting to take shape.”

While the broader community will likely continue to reference Tasmania as one appellation, more and more viticulturists, winemakers and sommeliers are beginning to recognise the subregions. “We’ve made a conscious decision to make wines that are reflective of this site and this part of the world. That’s how we treat the winery viticulturally. I’m sure the next person you talk to will say something completely different, but that’s how we do it here.” Let’s see what Champagne has to say.