Cask wine producer Ashley Ratcliff from Ricca Terra in the Riverland ponders the green credentials of cask wine.

I am fortunate to have experienced many aspects of the wine game, from planting vineyards and driving trucks through to selling wine across Australia and abroad.

In recent times I have read, heard and been told that wine consumers want wine grown, made and packaged in a sustainable manner.

Much of this noise is coming from the academic corner of the room.

While I am a full supporter of this movement – Ricca Terra was an early adopter of the Australian Wine Research Institute’s Sustainable Winegrowing Australian certification – my ‘in-market’ (bottle shops and restaurants) observations tell a different story.

Many wine drinkers are uncertain about what they really want when it comes to sustainable packaging, and many of those who are trying to tell the sustainability story (café and restaurant managers/owners; referred to as the customers in this paper) either don’t know or are just struggling to survive.

What café and restaurant managers and owners need is not a fairytale of how to save the world, they need hard facts on how best to stay afloat and protect and build their business.

Walk into any bottle shop and you will be confronted by a sea of glass bottled wines.

Sure there is a section for cask wine and wine sold in cans, but these selections are usually found at the back of the store, representing a small portion of what is on sale.

Try to find a wine on a restaurant’s wine list that comes in anything except a glass bottle. Good luck with that.

The bottom line is, as an industry – growers, winemakers, researchers, marketers and the like – we talk about sustainability among ourselves.

We have convinced ourselves that wine in cask, can and keg will have the punters giving up wine in glass and doing their bit to reduce carbon emissions by buying wine in cardboard.

Those reading this, who source their income by wearing out shoe leather via selling wine, know many ideas conceived by ‘blue sky thinking’ or via some market research programs simply do not work unless everyone from vineyard to glass is on board.

This is a perfect example of Marketing Myopia (a nearsighted focus of selling products or services, rather than seeing the big picture of what the customer really wants).

So what does the customer want?

Maybe they don’t know because we have failed to ask or educate them.

If we really want our customers to embrace sustainable wine packaging, we need to tell them the benefits.

They want to hear how they save money and generate revenue.

Get that right and the environmental stuff will follow – plus provide great wine.

Some facts

There is no questioning (scientific research proves it), that if wine consumers were hellbent on reducing carbon emissions or reducing waste, they would be drinking wine from vessels other than glass, such as cask, can or keg.

The Australia Wine Research Institute published a paper in 2016 titled ‘Assessing the environmental credentials of Australian Wine’.

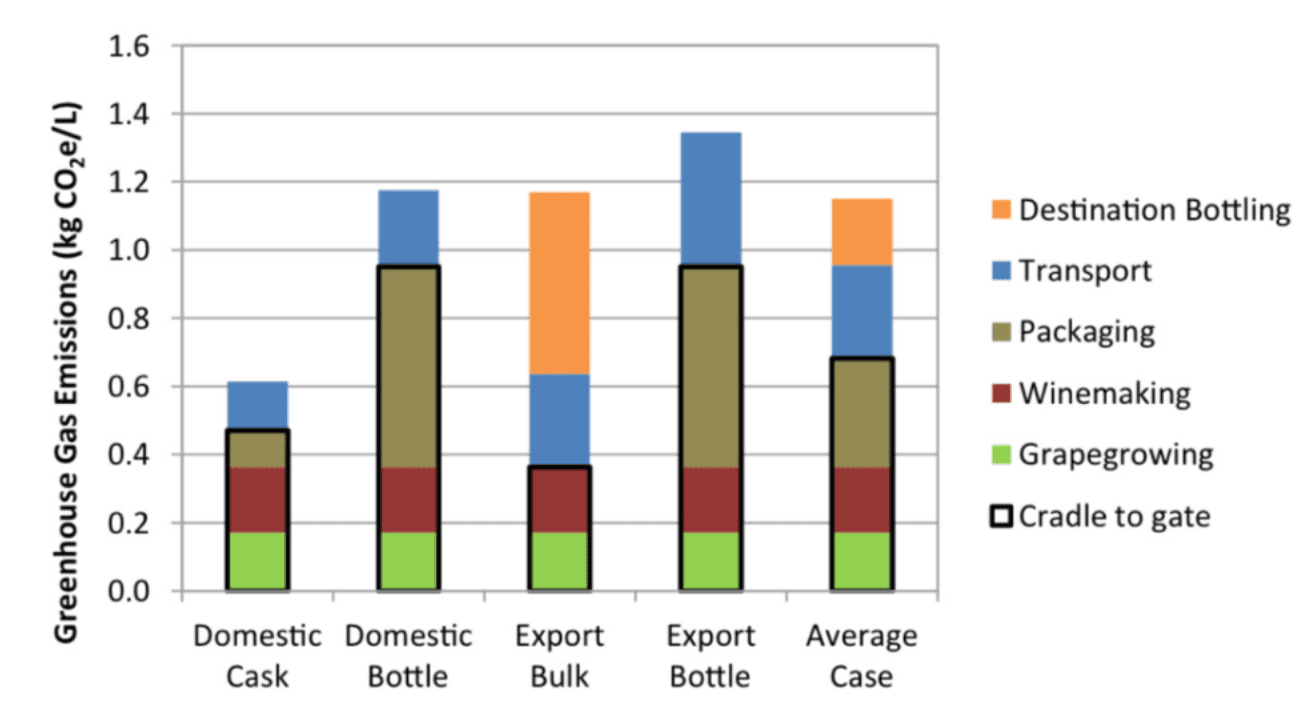

The graph below shows the large difference in greenhouse gas emissions between wine packaged in cask compared with glass.

Glass bottles require a large amount of energy to produce due to the high melting temperatures of the materials.

Cask packaging is much lighter and easier to produce. Cask wine is also a larger volume format, further contributing to lower emissions on a per litre basis.

There will be people that will state “glass can be recycled”. While this is true, a large portion of wine bottles end up in landfill or used as road base.

Build it and tell them …and they might come

Let’s forget for one minute all the environmental benefits of wine served in cask, can or keg and consider the challenges a manager or owner of a licensed café/restaurant face in today’s tough trading conditions.

Before certain groups of people attack me on the basis of the environmental credentials of non-glass vessels for wine, I accept that wine served in cardboard/bladders, metal and other forms of plastics also have issues that need ongoing improvement.

Challenge # 1: Wine wastage

Cafés and restaurants that are constantly open, have a high turnover of consumers, use wine protection systems (Corivan) or have owners/staff that take half-open bottles home for consumption experience little wine wastage.

But for cafés or restaurants that are closed for two or three days a week or have inconsistent numbers of patrons, wine wastage can be an issue.

According to a number of beverage managers I have contacted about the wine wastage problem, I concluded the wastage is estimated at five percent.

In dollar terms, that increases a bottle of wine with a landed unit price of $18 to $18.90.

This also equates to a wastage of 0.6 of a bottle per 12 bottle case.

Wine that is not exposed to air is at a lower risk of oxidation.

Wine in cask is not completely immune to oxidation as the bladder does have permeable characteristics.

Rule of thumb: wine served from cask will last for up to four to five months without noticeable impacts caused by oxygen, if stored appropriately.

What really counts? Revenue.

At my local wine bar the pour price per glass of wine (250ml) is $14. With an average wastage of 1.8 glasses per 12 bottle case (based on a five percent loss) the financial loss equates to $25.20 per 12 bottle case.

My local wine bar, which is not open Monday to Wednesday, is rarely full of drinkers, and sells close to 350 cases of wine per year.

Of course not all 350 cases are sold on-pour, but approximately 35 percent is.

Using all of this information, the wastage of wine (in dollar terms) at my local drinking hole is around $3,087 per year. While this loss may not sound alarming, it is a leakage of cash that can be avoided.

Challenge # 2: Waste disposal

Employers have the legal responsibility to ensure the health and safety of their workers, including managing the risk of lifting and moving objects. According to the Occupational Health & Safety Regulations (2017), employers must identify any task that involves hazardous manual handling, and then take actions to either eliminate or reduce the hazard.

During a recent visit to one of my favourite wine bars in Brisbane, I found myself discussing the costs of disposing empty wine bottles with the owner. The conversation was prompted by three waste disposal bins, waiting for collection, located out the front of the venue. The financial cost of disposing empty wine bottles was $63 per week ($3,276 per year) according to the owners records (based on three bins collected every week). On my arrival back home, I decided to establish some data re disposing of wine bottles. Here is how my ‘rural’ experiment went.

- I filled a green recycle bin (similar to that used at the wine bar in Brisbane with empty wine bottles to the brim). In total 130 bottles fitted in the bin, weighing 65kg. Already we have a manual handling issue.

- The total volume of wine in 130 bottles equals to 97.5 litres. This volume of wine in a 3 litre cask represents 32.5 casks, weighing 6.5kg (empty box, bag and tap weighs 200g). A 3 litre wine cask is equal to 4 x 750ml bottles, which represent only 50g/750ml of wine where as a glass bottle for the same volume weighs 500g (basically wine in cask weighs far less than glass… sorry for all the numbers). Packed properly, three bins worth of wine bottles can be replaced with one bin full of empty casks, resulting in a $42 per week saving in disposal costs ($2,184 per year saving).

Challenge # 3: Space management

It’s a luxury to have space. Space to store wine, space to chill wine and space to place empty bottles. Rent in many instances is charged by the square metre, so utilising space to generate revenue is essential. Even space to transport wine all comes as a cost. Let’s talk transport quickly. A pallet of wine in glass represents 576 litres (64 x 9 litre cases/pallet). The cost to transport a pallet of wine to Sydney from Adelaide is approximately $400 ($0.7/litre). There are 300 x 3 litre casks per pallet (900 litres). Wine in glass or cask takes up the same pallet footprint on a truck, hence both cost $400 per pallet for the trip. The cost to transport wine in cask is $0.44/litre (a $0.30/litre saving over glass). These savings can be retained by the wine producer or passed onto the customers. Either way the saving in transporting wine via cask over bottle is considerable.

As outlined earlier, a 3 litre cask is equivalent to 4 x 750ml bottles, yet a cask takes up the same footprint on a shelf or in a fridge as 2 x 750ml bottles. While I have not worked out the actual math, there are surely savings in refrigeration, stocking and internal storage of wine on a per litre basis. While I expect the saving to be small, over time they compound and contribute to a business’s margin.

Leaving quality to last… plus the hangover.

One of the greatest barriers stopping cask, can and keg wines growing in popularity is their perceived quality. In one of my previous lives, I managed a significant cask filling facility. The wine used to fill the casks were at the lower quality end compared to the other wines made and sold in bottle by the company that employed me. In stating this, the quality of wine used was still very good. Unfortunately this is not the case for all cask wines, and hence where the quality image started and continues.

Just imagine if Penfolds Grange Hermitage was sold in cask. The quality image/issue of this wine vessel would disappear overnight. There is also the question, from some consumers, that cask wine contributes to more severe hangovers due to the increased use of sulphur. Wine bottled in glass occurs under inert conditions (no/little air). When casks are filled there is an unintentional ‘slug’ of air that enters the bladder. To manage any potential spoilage issues, the level of sulphur added is greater than bottled wine (10-15 percent more). This additional sulphur is quickly bound-up, so issue with high sulphur levels and more intense hangovers is potentially personal problem, associated with lower quality cask wines or the consumption of too much alcohol.

The final words

At the production end of our industry we bang on about the benefits to the environment when talking wine sold in cask, can or keg. We think everyone along the value chain thinks the same way, but from what I have observed, for those on the front line selling wine, the focus is survival.

If I owned a café or restaurant, similar to that of my local wine bar, I would buy wine on the basis of:

1. Mitigates wastage and hence lifting revenue;

2. Reduces costs associated with disposal of empty wine bottles;

3. Protects myself and my staff from manual handling risks;

4. Makes the most of the limited space in my venue;

5. Wine quality that my customers like and are willing to re-order;

6. And finally… is good for the environment.

Small restaurant owner Jon Yeatman of Juan’s Torta Cantina in Bowden in South Australia says: “We all know the environmental standpoint of sustainable packaging, but for me cask wines are all about taking the worry out of logistics, waste, ease of use and storage. They have been a huge hit for our business and customers.”

• Ashley Ratcliff has spent over 30 years working in the Australian wine industry, starting in corporate vineyard management and then working through winery and operational management roles. Today Ashley owns Ricca Terra and the Wacky Grape Wine Company, travelling across Australia and the world marketing and selling wine made by Ricca Terra.

Further reading

The Australian Ark author wins Wine Communicator of the Year

Recent Comments